Open feedback loop

In 2003, officials in Garden Grove, California, a community of 170, 000 people wedged amid the suburban sprawl of Orange County, set out to confront a problem that afflicts most every town in America: drivers speeding through school zones.

In 2003, officials in Garden Grove, California, a community of 170, 000 people wedged amid the suburban sprawl of Orange County, set out to confront a problem that afflicts most every town in America: drivers speeding through school zones.

Local authorities had tried many tactics to get people to slow down. They replaced old speed limit signs with bright new ones to remind drivers of the 25-mile-an-hour limit during school hours. Police began ticketing speeding motorists during drop-off and pickup times. But these efforts had only limited success, and speeding cars continued to hit bicyclists and pedestrians in the school zones with depressing regularity.

So city engineers decided to take another approach. In five Garden Grove school zones, they put up what are known as dynamic speed displays, or driver feedback signs: a speed limit posting coupled with a radar sensor attached to a huge digital readout announcing “Your Speed.”

The signs were curious in a few ways. For one thing, they didn’t tell drivers anything they didn’t already know—there is, after all, a speedometer in every car. If a motorist wanted to know their speed, a glance at the dashboard would do it. For another thing, the signs used radar, which decades earlier had appeared on American roads as a talisman technology, reserved for police officers only. Now Garden Grove had scattered radar sensors along the side of the road like traffic cones. And the Your Speed signs came with no punitive follow-up—no police officer standing by ready to write a ticket. This defied decades of law-enforcement dogma, which held that most people obey speed limits only if they face some clear negative consequence for exceeding them.

In other words, officials in Garden Grove were betting that giving speeders redundant information with no consequence would somehow compel them to do something few of us are inclined to do: slow down.

The results fascinated and delighted the city officials. In the vicinity of the schools where the dynamic displays were installed, drivers slowed an average of 14 percent. Not only that, at three schools the average speed dipped below the posted speed limit. Since this experiment, Garden Grove has installed 10 more driver feedback signs. “Frankly, it’s hard to get people to slow down, ” says Dan Candelaria, Garden Grove’s traffic engineer. “But these encourage people to do the right thing.”

In the years since the Garden Grove project began, radar technology has dropped steadily in price and Your Speed signs have proliferated on American roadways. Yet despite their ubiquity, the signs haven’t faded into the landscape like so many other motorist warnings. Instead, they’ve proven to be consistently effective at getting drivers to slow down—reducing speeds, on average, by about 10 percent, an effect that lasts for several miles down the road. Indeed, traffic engineers and safety experts consider them to be more effective at changing driving habits than a cop with a radar gun. Despite their redundancy, despite their lack of repercussions, the signs have accomplished what seemed impossible: They get us to let up on the gas.

In the years since the Garden Grove project began, radar technology has dropped steadily in price and Your Speed signs have proliferated on American roadways. Yet despite their ubiquity, the signs haven’t faded into the landscape like so many other motorist warnings. Instead, they’ve proven to be consistently effective at getting drivers to slow down—reducing speeds, on average, by about 10 percent, an effect that lasts for several miles down the road. Indeed, traffic engineers and safety experts consider them to be more effective at changing driving habits than a cop with a radar gun. Despite their redundancy, despite their lack of repercussions, the signs have accomplished what seemed impossible: They get us to let up on the gas.

The signs leverage what’s called a feedback loop, a profoundly effective tool for changing behavior. The basic premise is simple. Provide people with information about their actions in real time (or something close to it), then give them an opportunity to change those actions, pushing them toward better behaviors. Action, information, reaction. It’s the operating principle behind a home thermostat, which fires the furnace to maintain a specific temperature, or the consumption display in a Toyota Prius, which tends to turn drivers into so-called hypermilers trying to wring every last mile from the gas tank. But the simplicity of feedback loops is deceptive. They are in fact powerful tools that can help people change bad behavior patterns, even those that seem intractable. Just as important, they can be used to encourage good habits, turning progress itself into a reward. In other words, feedback loops change human behavior. And thanks to an explosion of new technology, the opportunity to put them into action in nearly every part of our lives is quickly becoming a reality.

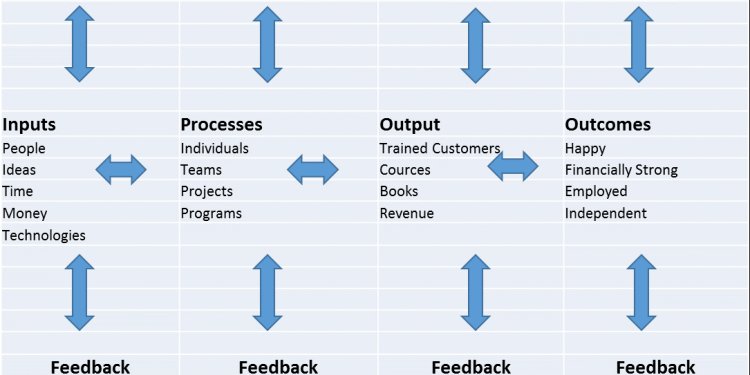

A feedback loop involves four distinct stages. First comes the data: A behavior must be measured, captured, and stored. This is the evidence stage. Second, the information must be relayed to the individual, not in the raw-data form in which it was captured but in a context that makes it emotionally resonant. This is the relevance stage. But even compelling information is useless if we don’t know what to make of it, so we need a third stage: consequence. The information must illuminate one or more paths ahead. And finally, the fourth stage: action. There must be a clear moment when the individual can recalibrate a behavior, make a choice, and act. Then that action is measured, and the feedback loop can run once more, every action stimulating new behaviors that inch us closer to our goals.

This basic framework has been shaped and refined by thinkers and researchers for ages. In the 18th century, engineers developed regulators and governors to modulate steam engines and other mechanical systems, an early application of feedback loops that later became codified into control theory, the engineering discipline behind everything from aerospace to robotics. The mathematician Norbert Wiener expanded on this work in the 1940s, devising the field of cybernetics, which analyzed how feedback loops operate in machinery and electronics and explored how those principles might be broadened to human systems.